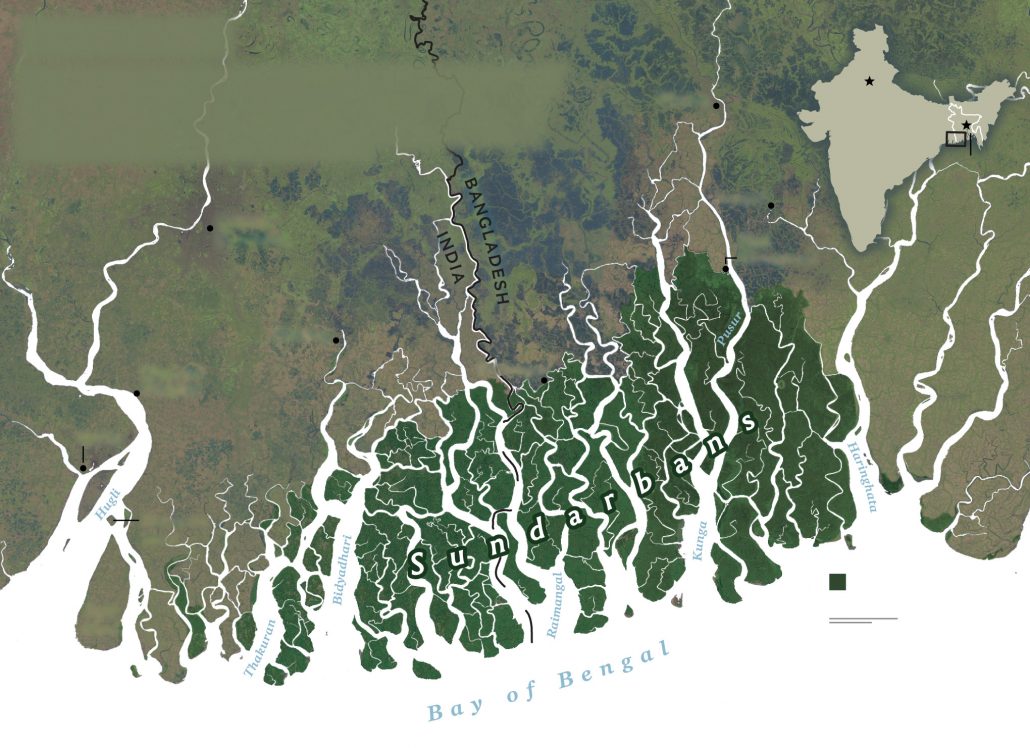

The Sundarbans, the world’s largest single-track mangrove forest, is located in the southern coast of Bangladesh and northeastern India. The total area of the forest is about 10 000 km², of which 62% belongs to Bangladesh and 38% in India. This forest usually feeds the river Ganges and hundreds of its tributaries. The inhabitants of the surrounding areas, mostly living below the poverty line and the forest is an abundant source of subsistence for them.

The best time to visit Sunderbans is from October to February during the dryer, cooler winter months. When the monsoon rains wake up, there is a risk of floods and hurricanes and not suitable for a visit there.

Sunderbans is very famous for a variety of biodiversity. It includes 334 species of plants, 282 species of birds, 49 species of mammals, 63 species of reptiles, 210 species of fish, and 10 each species of amphibians and molluscs. The forest also hosts several endangered species, such as the Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris), Gangetic dolphins (Platanista gangetica), and the Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus).

The Sundarbans has varieties of forests, including mangrove scrubs, salt water mixed forests, littoral forests, brackish water mixed forests and swamp forests. Bruguiera spp., Ceriops spp., Xylocarpus spp., Avicennia spp., Rhizophora spp., Sonneratia spp., are some of the mangrove species in there. This mangrove ecosystem plays an essential role as a breeding ground and nursery for the coastal fishing industry in the Bay of Bengal.

Sunderbans provides a natural barrier that protects people in the region from tidal waves and hurricanes and has saved more than 10 million lives from hurricanes over the last couple of decades.

In 1992, about 601,700-hectare of forest reserve in Sunderbans, Bangladesh was declared as a Ramsar site. The Sundarbans was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 due to its wildlife and unique ecosystem.

Under the pressure of land loss, people are encroaching animal habitats, cutting down trees for farmlands. Due to human encroachment and climate change, the forest has been losing 16 square kilometers of vegetation per year since 1991, and the habitat of the animals is under the threat. The 2004 census estimated the number of tigers in the Sunderbans is around 440, and the population was gradually declining.

“We must do everything possible to save the remaining population and help people and tigers to coexist,” says Raquibul Amin, Bangladesh country director for the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Rising sea levels swallowing the forest, while increasing salinity is damaging plants and marine life. Scientists warn that a continuous coastal recession could lead to the disappearance of large mangroves in the next 50 years.

On human stress, a new threat to this fragile ecosystem is an ongoing coal-based power plant that has been approved bypassing the requirements for public participation and environmental impact assessment. Human interventions such as up-stream agriculture, logging, industrial shrimp farming, and hydrological interventions are conducing to degradation of the mangrove ecosystem.

Didarul Absar, founder of Bangladesh Eco Tours, emphasizes that tourists should use local tour operators. They must also respect wildlife and the environment: do not litter, care for noise pollution, and do not disturb the animals.

The bilateral cooperation between Bangladesh and India and the Ramsar Convention have enhanced the conservation strategies of the Sundarbans over the past decade. Experts emphasize, it is extremely important to avoid human pressure on the wetland and its resources by considering the environmental issues when setting up industrial projects near mangrove forests.

Cover Photo : Arco Datto